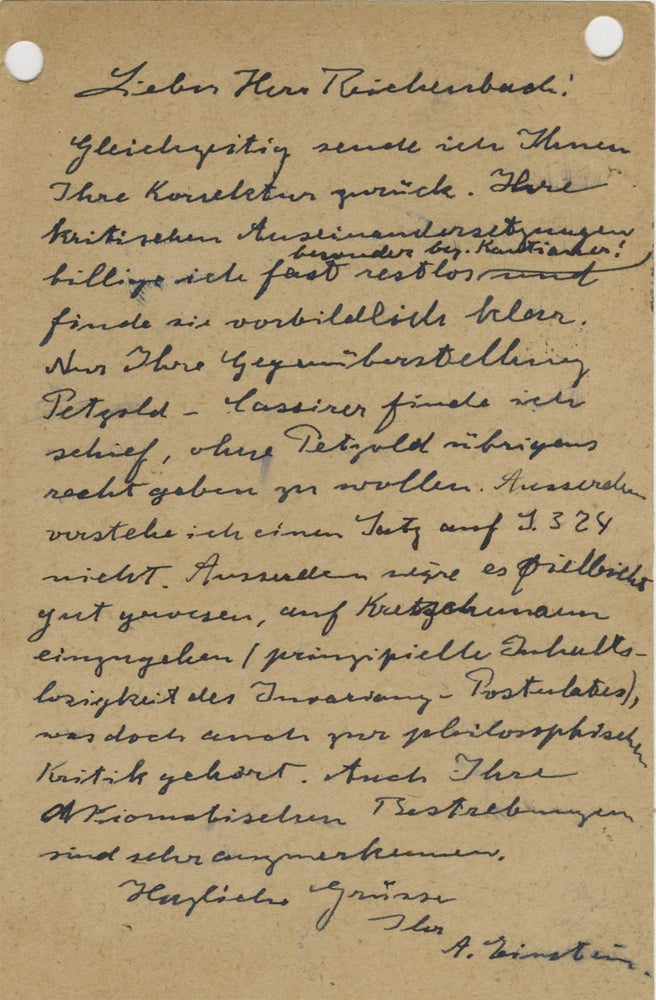

Autograph Letter Signed

EINSTEIN WRITES TO THE AUTHOR OF A BOOK ON RELATIVITY, CRITIQUING HIS ARGUMENTS.

In early 1922, Einstein had received a proof of the scientific philosopher Dr. Hans Reichenbach's paper "The Current State of Discussions on Relativity. A Critical Investigation” and, in this letter, dated March 27, 1922, Einstein offers his opinion of the work to Reichenbach.

The text (translated from the original German) reads in full:

Dear Mr. Reichenbach:

At the same time, I send your correction proofs back to you. I agree almost entirely with your critical argumentation, particularly in re. Kantians! and find it exemplarily clear. It is just your disagreement with both Petzold and Cassirer that I find to be off the mark, without, by the way, wanting to give any credit to Petzold. Nor do I understand a sentence on p 324. Additionally, it would perhaps have been good to discuss Kretschmann (fundamental vacuousness of the invariance postulate), which also really does merit philosophical criticism. Your axiomatic endeavors are very laudable as well.

Cordial regards, yours,

[signed] A. Einstein.

---------------------------

Background on the letter:

Although on December 10, 1921, Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, and he would accept that prize one year later, not everyone accepted relativity. A few prominent scientific detractors sought to reconcile what they saw as inconsistencies and "correct" Einstein's work. Others sought to analyze it through the lens of theoretical space-time and the long running debate on the nature of space and time, while some philosophers attempted to determine its relation to important philosophical concepts.

Hans Reichenbach was a well-known scientific philosopher, now famous for his investigative analyses of Einstein’s Relativity. He set himself in the middle of this debate. The timing of Reichenbach’s work was not coincidental. He believed that “modern” physics was concerned with problems that, until the late 19th century, were regarded as philosophical, for example, the nature of space and time, the source of gravitation, the real extent of causality. The great philosophers of eras past were in many cases scientists, but the progression of science had separated the two fields. And men like Einstein, who had crafted scientific theories around objective scientific principles, did not always concern themselves with matching them to age-old propositions. This Reichenbach aimed to do, and to arrive at certain axioms that would prove true and help answer the questions: What is space? What is time? This was, after all, the essence of Einstein’s work and his greatest legacy.

Reichenbach’s work was largely supportive of Einstein. In the early 1920s, just a few years after Einstein’s Theory of Relativity was proposed and immediately after he received the Nobel Prize, Reichenbach began his work. In it, he attempted to create an axiomatic approach to Relativity, where it could be broken down into its smallest and most universally true component parts. What is the core of Relativity? He rejected the Kantian theory, and felt that Einstein had correctly shown how to measure the various elements that go into the formulation of space and time. He wrote, “The radical Kantians do not want to admit that Einstein’s theory refers to the content of the intuition of space and time; they maintain that the theory concerns only the measurement of space and time magnitudes, not space and time proper…. the Neo-Kantians… merely dogmatically assert that an empirical theory cannot affect pure intuition. They nowhere attempt to relate the empty and untouchable a priori to the observable world, to empirical knowledge.”

Ernst Cassirer was another German philosopher who was, in essence, a Neo-Kantian, attempting to reconcile Kant with evolving scientific principles. Reichenbach wrote about him, “It is Cassirer’s great achievement to have awakened Neo-Kantianism from its ‘dogmatic slumber… I see Cassirer’s merit in the fact that he… did not evade modern physics like other Kantians.” Cassirer essentially evolved Kant’s philosophy to make it consistent with Relativity, and this pleased Reichenbach. “Nevertheless,” Reichenbach wrote, “I maintain that such an approach is tantamount to a denial of synthetic a priori [Kantian] principles.”

Joseph Petzold was a positivist, who sought to conform older scientific theories to the new world of science, where something was valid if it could be measured or somehow proven. Making antiquated theories consistent with Einstein’s world led Petzold astray.

Reichenbach opposed viewpoints published by both Petzold and Cassirer concerning the nature of space and time — in particular, Petzoldt’s opinion that Einstein’s general theory of relativity supports Ernst Mach’s view that there is no “absolute” in a theory, that everything is relative or subjective. Einstein finds Reichenbach’s discussion of Petzold and Cassirer to be somewhat biased.

Another point touched on by Reichenbach relates to German scientist Emile Kretschmann. Einstein required that General Relativity be formulated using physical quantities (such as velocity or position) that can be transformed in certain mathematical ways such that they’re correlated with one another. In this way, there’s no absolute space-time, but different points of view are perfectly correlated with one another and observations are not purely subjective. Kretschmann stated that this “covariance” requirement is useless, since it does not actually affect the types of theories that can be constructed. Einstein and Kretschmann disagreed on this point, and Einstein suggested that Reichenbach might include a discussion based on this philosophical disagreement regarding covariance, something he evidently considered very worthy of analysis.

Reichenbach’s grand goal was to place Einstein the scientific-philosopher lineage that had for centuries tried to define the nature of space and time. In doing so, he states that Einstein knew that his work was philosophical in nature. Reichenbach aimed to prove that, “It would be erroneous to say that Einstein’s contribution consists only in the establishment of a physical theory; he has always been aware of the fact that his theory is based upon a philosophical discovery.” His analyses of Einstein remains among the most respected contemporary works on this subject.

Berlin, March 27, 1922, the verso addressed in Einstein’s hand "Herr Dr. Hans Reichenbach, Physikal Institut.” One page.

It is extremely rare to find a letter by Einstein in which he collaborated in this way on a work analyzing his own theories and adding his own ideas; the letter also demonstrates the important point that Einstein agreed that his work had a strong philosophical component.

Check Availability:

P: 212.326.8907

E: michael@manhattanrarebooks.com